The V-2 Rocket Story

The Beginning of the Space Race

Wernher von Braun (in suit) with German officers in 1941.

Chief of the SS Heinrich Himmler (center) during a visit to the Peenemünde Army Research Center, June 1943.

German military leaders believed liquid-fueled rockets could replace conventional weapons and would also allow for larger payloads with greater range. If this type of new weaponry could be kept secret, it would have the added benefit of terrorizing the populace of Germany’s enemies. Third, there was already public interest in rockets and rocket social groups existed. Some of those groups were backed by renowned scientists.

One rocket society was the Verein fur Raumschiffahrt (VfR), or Society for Space Travel, created in 1927. Not just a society filled with intellectuals, the founders also had a flair for the dramatic. Creating “rocket” race car demonstrations that gained publicity. While the VfR had the talent, they lacked the funding and hoped to find a wealthy benefactor, never dreaming that the Germany military would be their provider. A young engineer, Dr. Wernher von Braun joined the VfR and worked closely with his mentor, Dr. Oberth. The army agreed to help fund the VfR program, but only under the veil of secrecy, with no more publicity stunts allowed.

In December 1932, von Braun began working with the German Army. Two months later, Hitler came to power. By December 1934, von Braun and his team had proven they could launch a rocket, then known as the A-2. All Germany needed now was a site where all design and testing could happen under one roof.

“If I had had these rockets in 1939, we should never have had this war...Europe and the world will be too small from now on to contain a war.

— Adolf Hitler to Wernher von Braun and General Dornberger after watching film of the first successful V-2 flight

World War II and the V-2

German V-2 rocket and launch tower, 1945.

V-2 test launch.

The two major leaders in the development of the V-2 rocket share a personal moment. General Walter Dornberger (left) oversaw the military logistics and financing of the rocket. Dr. Wernher von Braun (right) led the technological development of the rocket. Both shared the vision that the rocket was more than a weapon of war; it also created a road for humankind to the stars.

One of the earliest investments the German army made in the V-2 rocket was to build the Peenemünde Army Center in 1937. The site was perfect. It was in a remote area, which provided a level of secrecy and security. It also had an offshore island. A launch site surrounded by water further helped to conceal the program.

Prior to World War II, Peenemünde was a small, sleepy, German island fishing village just off the coast of the Baltic Sea. By the middle of the War, it was one of Germany's largest and most top-secret military complexes. Here, the German war machine focused its physical and financial energy on the creation of Hitler's most infamous secret weapons - the V-1 "Buzz Bomb" and the V-2 rocket.

The development of the V-2 pushed the limits of warfare production. After years of frustrating failure and immense amounts of money, manpower, and materials, the Germans finally developed the necessary science and engineering for the missiles to live up to their potential. On October 3, 1942, the first successful launch of a V-2 rocket was achieved from the Peenemünde test site.

“Do you realize what we accomplished today? Today, the spaceship has been born!”

Hitler ordered the V-2 missiles into full-scale production at Peenemünde. But before the large production plants could be completed, the German missile program experienced a major blow.

On the night of August 17, 1943, the British Royal Air Force (RAF) conducted its first bombing raid on Peenemünde, with the code-name "Operation Hydra." Britain, which had sustained 40,000 civilian casualties between September 1940 and May 1941 alone during the German bombing campaign known as the Blitzkrieg, or Blitz, had received intelligence reports relating the potential of Germany’s V-2 program. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill knew stopping the production of the Vengeance weapons was critical and approved risking nearly the entire RAF bomber fleet to wipe out the target.

Nearly 500 British bombers were sent against Peenemünde. Damage was heavy, and more than 700 casualties were experienced, including several key scientists and engineers. More than 550 of those killed were foreign prisoners, who were locked in their barracks to prevent their escape during the raid.

Operation Crossbow movie poster, 1965

Eventually, additional Allied bombing raids were sent against Peenemünde. Some raids numbered more than 600 bombers carrying nearly one million pounds of high explosives. The German missile program had become one of the Allies top priorities for destruction.

Operation Hydra was also known as Operation Crossbow. It was of such significance that it was the subject of a 1965 movie by the same name.

“We who gave life to Peenemünde deplore as much as anyone that rocket development has been applied to destructive purposes rather than for human benefit.”

— Wernher von Braun

Peenemünde to Nordhausen

V-2 German Launch, 1944.

A rare color photo of one of Nordhausen’s main underground tunnel galleries under construction.

Nordhausen prisoner liberated by Allies.

Heinrich Himmler, the Reich Leader of the SS, argued that spies had given away the Peenemünde location and suggested they move production underground and use only prisoners for assembly.

The Germans found a ready-made facility to move the missile program production into the Harz Mountains, near Nordhausen in central Germany. The Nordhausen site consisted of a large series of mountain tunnels that had originally been built as an oil storage area. Here, the V-2 went into mass production in what was to become the largest underground factory in the world. While Nordhausen seemed to be ideal, V-2 production was delayed by many factors including air raids, subcontractors, and lack of materials. The prisoners also lacked the necessary skills and experience to build the V-2 rocket.

This photo shows prisoners laboring under the watchful eye of supervisors. These men were concentration camp inmates who had been transferred to Camp Dora from the notorious Buchenwald death camp.

Prisoners working on the V-2 experienced some of the worst conditions of any concentration camp. Initially, they slept in the tunnels and rarely saw the light of day. Tunnel conditions were deplorable. There was little food or water and no washing facilities or toilets. It was never warmer than 59°F (15°C) and dysentery, tuberculosis and pneumonia were rampant. The number of deaths was so high even the Nazis took notice of the abysmal conditions. Eventually, a concentration camp, known as Dora, was established above ground on the site. By the end of the war, the death tally at Dora was more than 20,000, which far exceed the number who died from V-2 bombing attacks.

“The lives of camp inmates are, by definition, expendable.”

— Arthur Rudolph, V-2 Chief Production Engineer

Life Saving Espionage

Damage caused by the London Blitz-V-2 rocket bomb incident at Chinatown, Limehouse, East London on March 2, 1945. Image credit: The Imperial War Museum

Map showing impact sites of the V-1 and V-2.

Targets of the V-2s included Belgium, Britain, France, Netherlands and Germany. In London, it is estimated that 2,754 civilians were killed by 1,402 V-2s launched.

Although a single V-2 could and did kill hundreds of people, many of the V-2s did not hit their targets. This was due in part to a spy network of German spies who were converted to work for Britain instead.

The only way the V-2 launch crews knew where their missiles were landing in London was by secret radio communications from German spies located throughout the city. The spies provided map coordinates of each impact back to the launch crews in western Europe who would use the information to further pinpoint the guidance system for the “V” weapons.

What the Germans did not know is that toward the end of the war, and by the time the V-2 blitz began on London, the Allies had captured many German spies and had turned them into double agents, who began transmitting inaccurate impact coordinates to Germany. The intelligence they sent back to Germany implied those that had succeeded in hitting London had missed their course by miles, thus redirecting many V-2 (and V-1) targets to be in the countryside or in the English Channel. So convincing were the German double agents used in this hoax, that one spy was awarded the German Iron Cross from Hitler, and later, the Victoria Cross from British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, for his “important’ work in providing secret information to help determine “V” weapon trajectories.

“At night, I would lie in bed and stare at the ceiling wondering if a (V-2) rocket were already on the way down.”

— Unknown Londoner during the V-2 blitz

V-2 Post World War II

German rocket engineer Wernher von Braun (with arm in cast) and his brother Magnus (second from right) after surrendering to the U.S. forces, May 2, 1945. Image: MSFC/NASA

American soldiers at Nordhausen.

It’s not surprising that, even before the war was over, the Allies were strategizing about how to obtain Germany’s new technology. But it wasn’t just the V-2 rockets they wanted, the Allies also needed the men who designed and built the rockets.

Enter Operation Paperclip (originally called Operation Overcast), a top-secret program launched by the American military in the fall of 1944 to obtain German technology and resources.

It was critical the Americans find the German weaponry including the V-2 and the engineers and scientists who built it before the Soviets did. Whichever country obtained these critical weapons and plans would have an edge in what appeared to be the threat of a war between the Soviet Union and United States.

Meanwhile, von Braun and his team knew Germany was crumbling and that they would have to surrender to either the Soviets or Americans. It is surmised that von Braun chose to put himself and his team in the hands of the Americans as he hoped they would be better treated and that they would have superior resources to continue their work in the United States. Once he surrendered, he and his colleagues helped the U.S. locate the V-2 hardware and engineering blueprints which were smuggled out by rail overnight before the Soviets arrived. This was prior to Germany’s surrender and to the Yalta Conference, so the allocation of war time materials and resources had not yet occurred.

Operation Paperclip was so named because the scientists and experts who surrendered to the military were carefully screened. Of them, 100 were chosen to come to the United States. They were distinguished from the others by a paperclip that was attached to their folders.

“Pay no attention to the human cost. The work must go ahead and in the shortest possible time.”

— General Hans Kammler

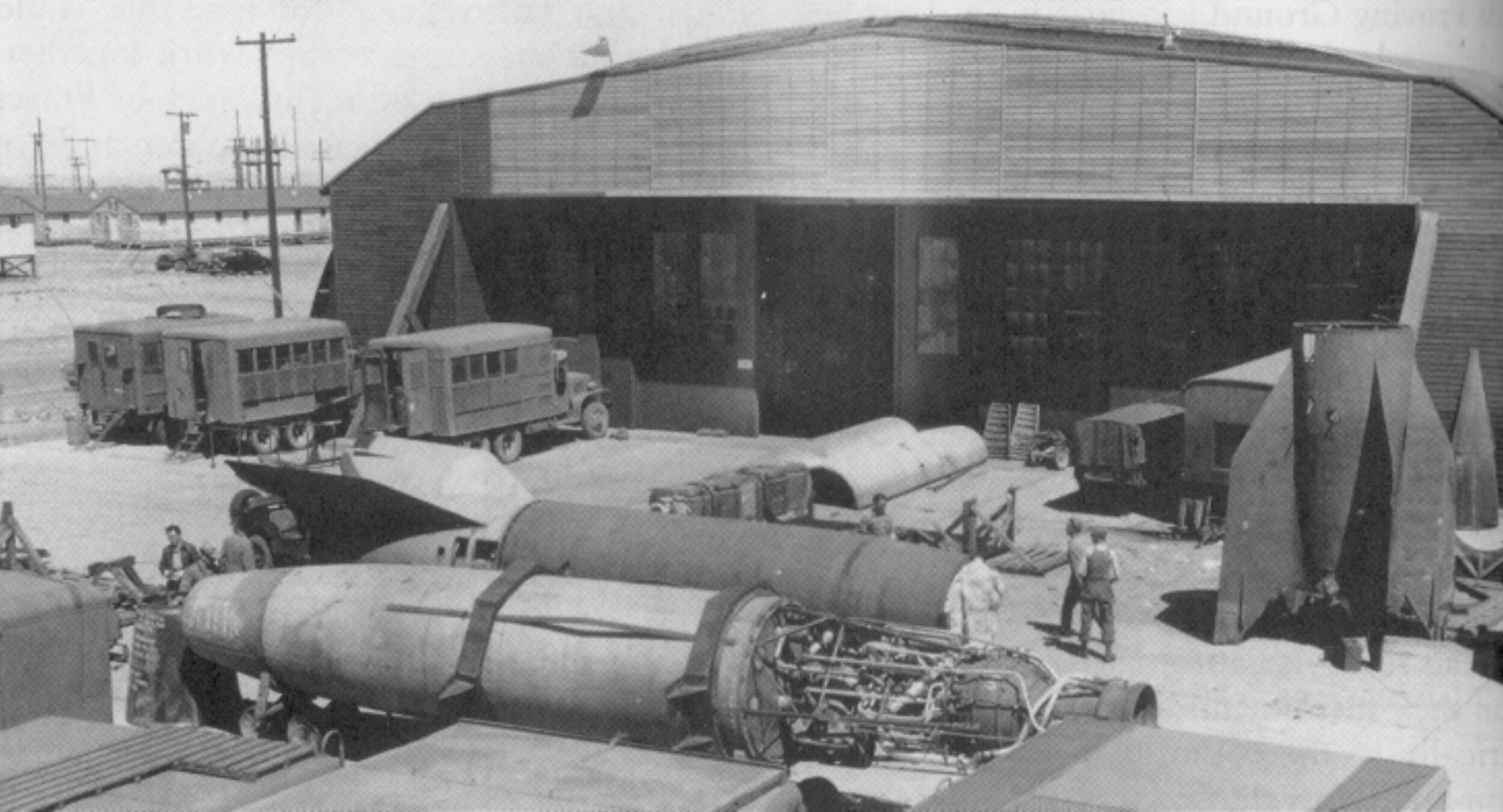

Fort Bliss and White Sands

104 Operation Paperclip rocket scientists in 1946, in Fort Bliss, Texas, after World War II.

V-2 at White Sands, 1946.

Finding a place to house the captured Germans and to continue the development and testing of the V-2 was the next order of business for the U.S. Military. The solution was to assign them to Fort Bliss, TX. For six-month periods 20 at a time would work at the White Sands Proving Ground in New Mexico to conduct live firings. On January 16, 1946, V-2 flight tests began at White Sands Proving Grounds and continued until 1949.